HTTP Request Smuggling for dummies

Introduction

Today, we are going to discuss a lesser-known vulnerability, HTTP request smuggling.

Behind this somewhat intimidating term, HTTP Request Smuggling, lies a very interesting vulnerability.

DISCLAIMER: For this blog post, I assume that you are technically familiar with the HTTP protocol. If you are not, I have released a video as well as a blog post on the subject.

Before delving into request smuggling, let's take a step back and review its versions (talking about HTTP) to better understand the origin of the vulnerability.

Previous Versions of HTTP

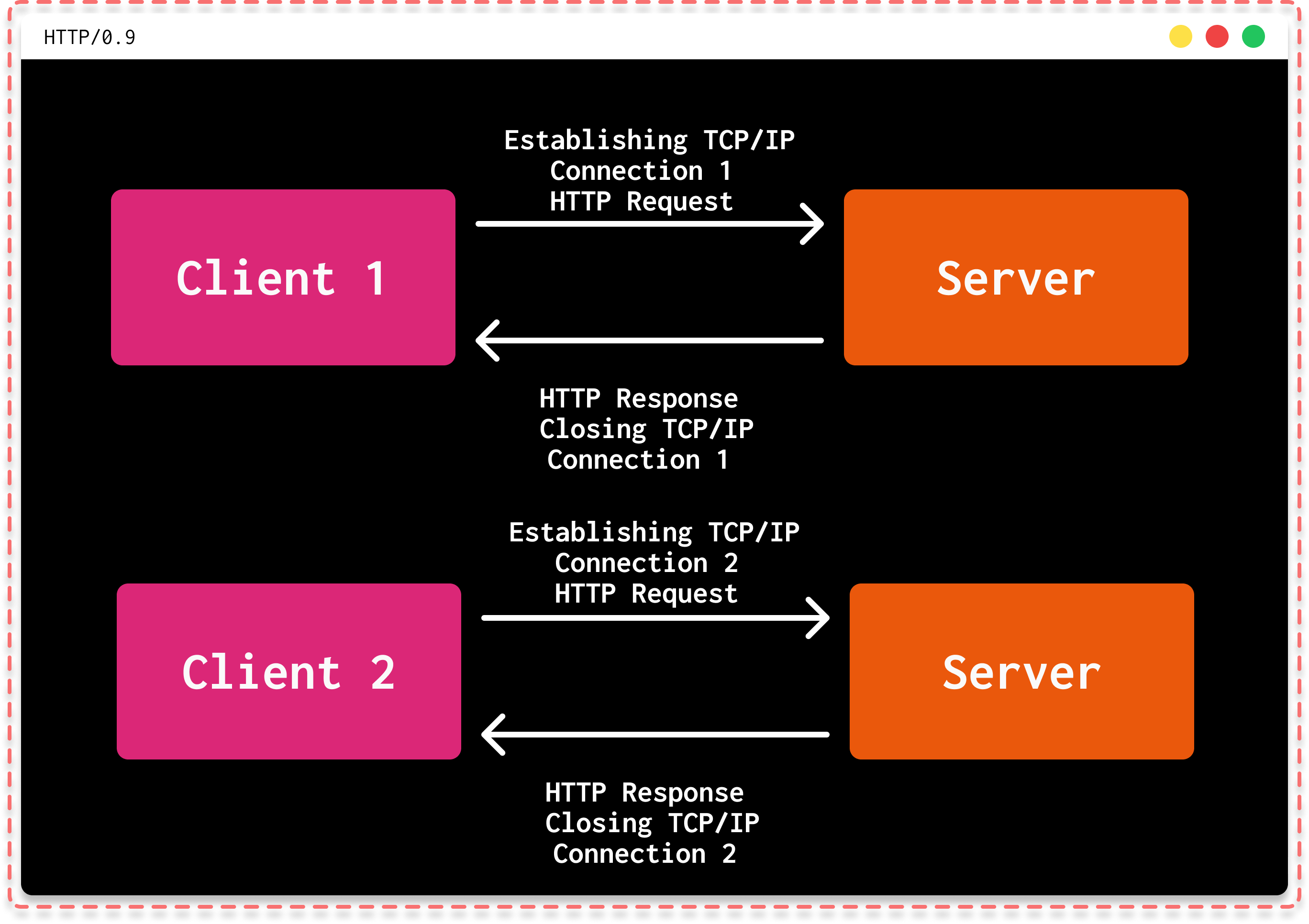

Version 0.9

It's important to note that in its 0.9 version, the only way to send 3 requests was to open 3 separate TCP/IP connections to the server and request the target document each time. As you can imagine, this was quite cumbersome and resource-intensive.

|

|---|

| How HTTP operated in version 0.9 |

HTTP has always been, and still is, a rather simple protocol, especially in its 0.9 version. Take note of the use of \r\n to represent the carriage return and line feed characters, which are line-ending markers. This will be important later on.

|

|---|

| Explanation of what \r\n is (used to mark the end of a line) |

Version 1.0

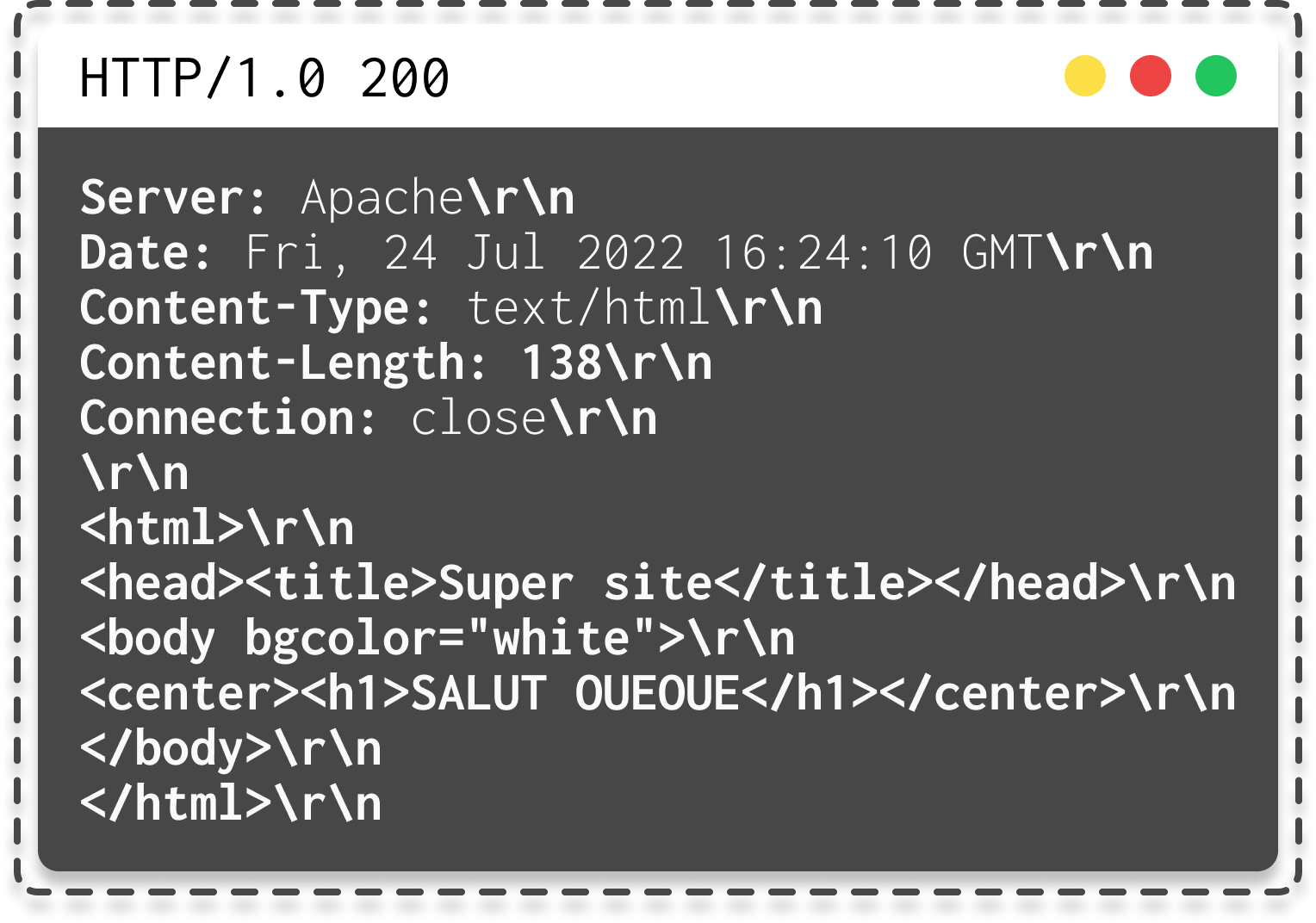

With the arrival of HTTP/1.0, a very important feature was introduced, as seen in the video and blog post on HTTP : headers. Here's the first request in HTTP/1.0:

|

|---|

| How HTTP operates in version 1.0 with \r\n displayed |

It's crucial to note the Content-Length header, which corresponds to the number of 7-bit ASCII characters starting from <html, including line-ending characters, totaling 138 bytes.

To fully understand request smuggling, remember that size matters (within the context of HTTP, of course).

Version 1.1

With the arrival of HTTP/1.1, three important features were added (especially for understanding request smuggling):

- Keep-Alive Mode

- Pipelined Requests

- Chunked Requests and Responses

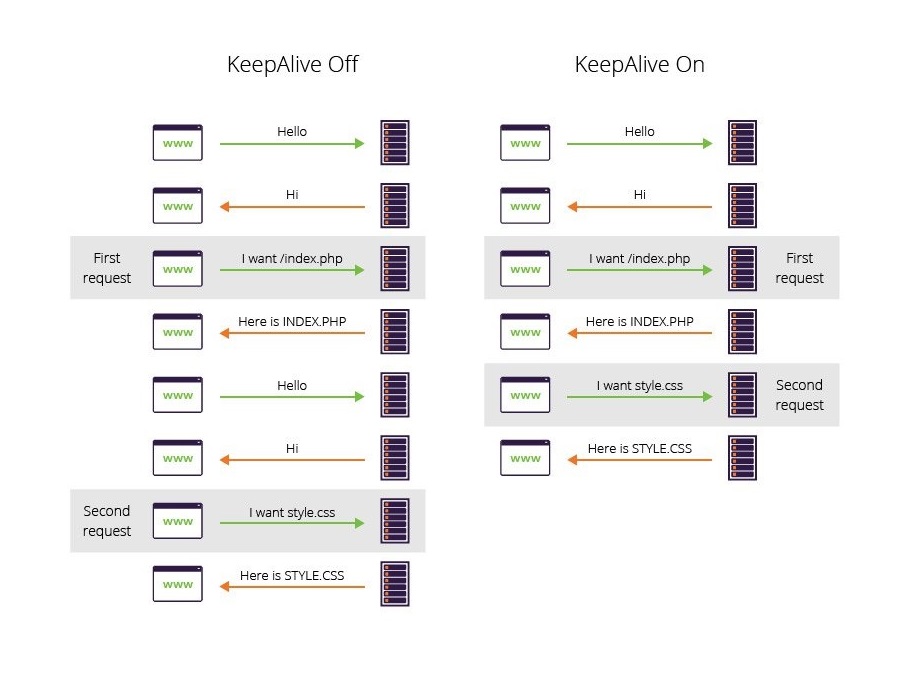

Keep-Alive

The Connection: Keep-Alive mode is a header that signals to the server that it can handle multiple requests/responses within the same TCP/IP connection.

As you can imagine, this changes significantly compared to version 0.9, where each request required opening a new TCP/IP connection.

|

|---|

| Fonctionnement du header keep-alive (source: imperva) |

It's also possible to specify Connection: Close, which instructs the server to terminate the connection after the first request/response exchange. However, remember that the Keep-Alive mode is widely used because it's often enabled by default on web servers to optimize connections.

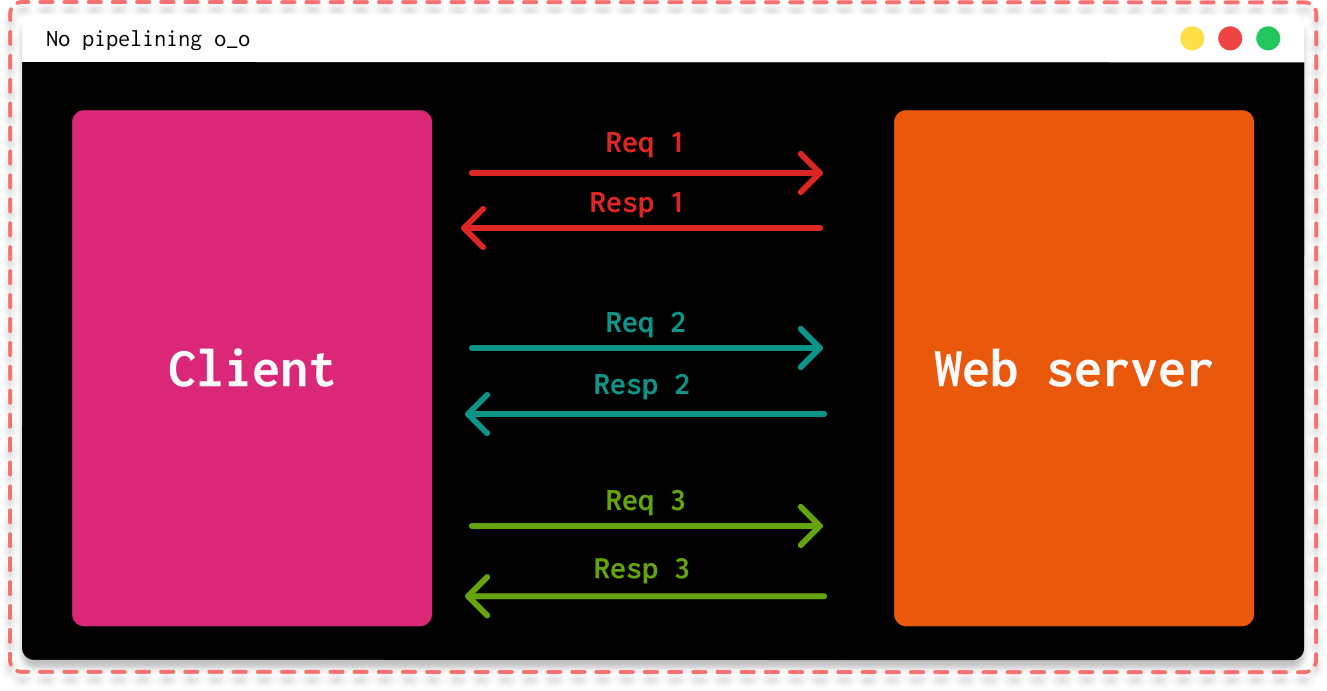

Pipelining

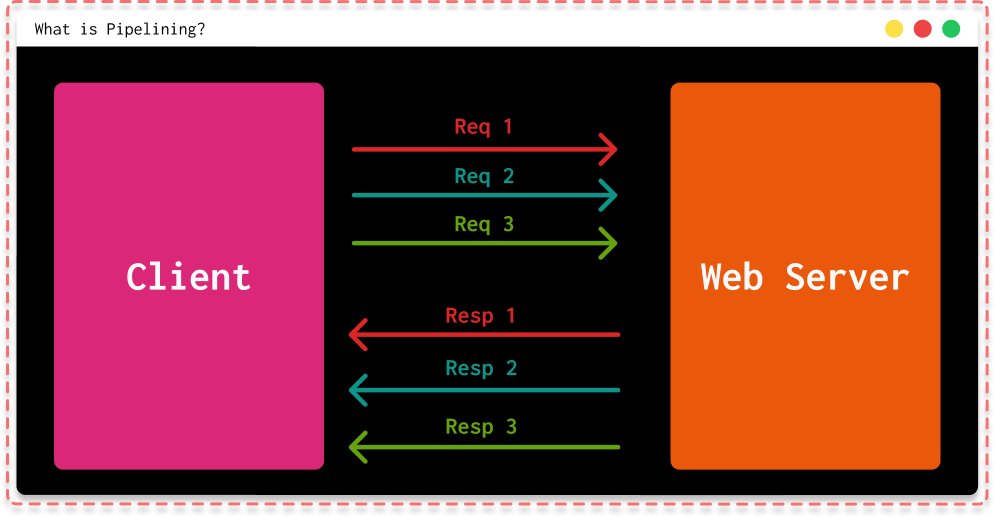

Another significant addition in this version of HTTP is pipelining. This concept involves bundling multiple HTTP requests into a single TCP connection without waiting for responses for each request. As you might have already understood, the operation of pipelining heavily relies on the Keep-Alive header mentioned just above.

|

|---|

| Pipelineless operation |

This greatly optimizes the speed of request/response because person B won't have to wait for person A's response to retrieve their own response!

|

|---|

| Operation with pipelining |

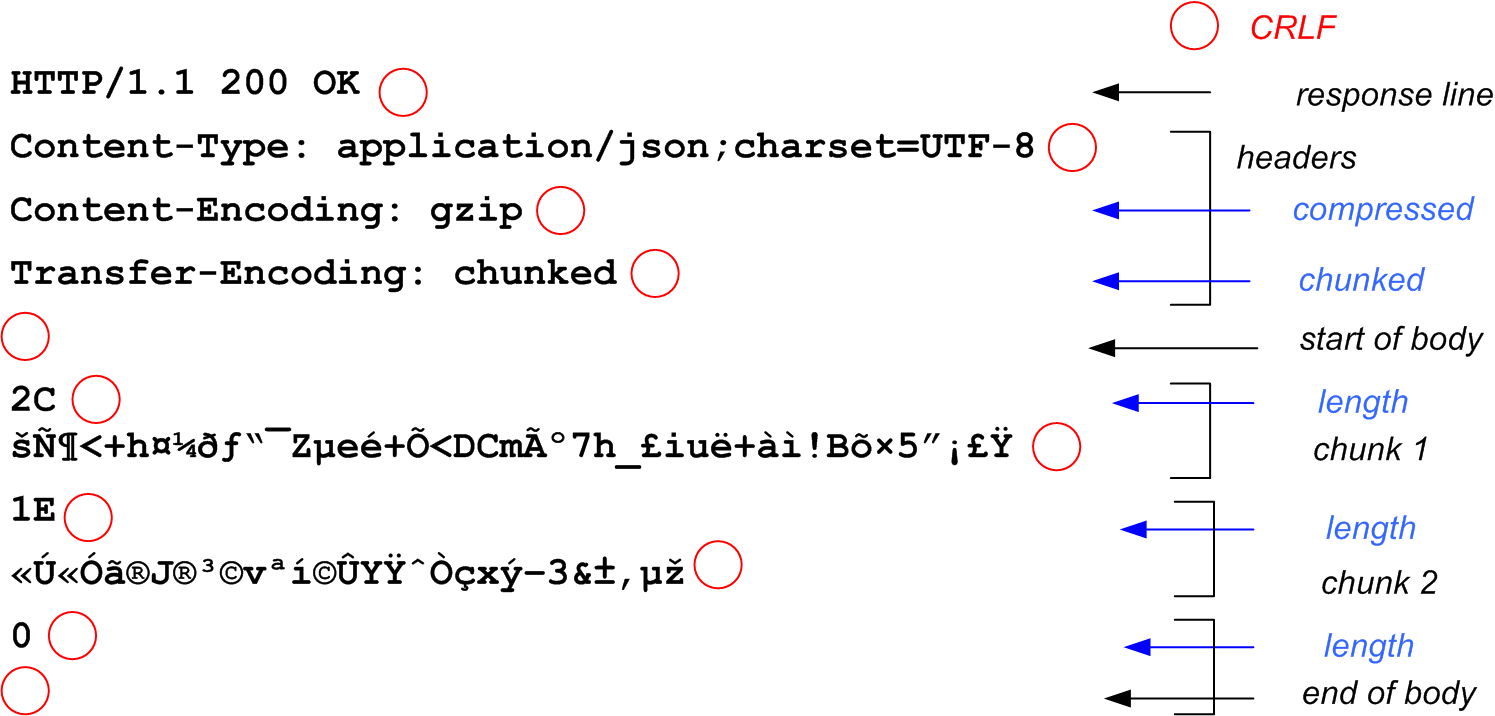

Chunks

Finally, in version 1.1, came the chunked transfer (Transfer-Encoding: chunked), which is an alternative to the Content-Length header.

While Content-Length announces the final complete size of the message (as seen previously), chunked transfer allows transmitting a message in several small packets (chunks). Each chunk announces its size using a special last chunk with an empty size to mark the end of the message. Once again, you'll notice the \r\n AKA CRLF.

|

|---|

| Representation of Chunks in an HTTP Request |

HTTP Request Smuggling

It was a bit lengthy, but now you have all the necessary information to understand request smuggling.

Let's recap:

- HTTP requests/responses are lists of strings separated by line-ending markers (carriage return).

- The HTTP agent that reads requests must know where this list of strings ends in order to separate different HTTP requests. To do this, the HTTP agent relies on the Transfer-Encoding or Content-Length header.

- Current web applications often work with both a front end and a backend.

- With Keep-Alive and pipelining, it's possible to send multiple requests over the same TCP/IP connection without waiting for responses.

In an architecture with a frontend and a backend:

When the frontend server forwards HTTP requests to a backend server, it typically sends multiple requests over the same TCP/IP connection, as we saw with pipelining.

Hence, the front end and back end must agree on the boundaries between requests, or else, an attacker could send an ambiguous request that is interpreted differently by the front and back ends.

HTTP Request Smuggling occurs when an attacker sends a request to the front end that contains two HTTP requests in one.

This may seem a bit unclear at the moment, but we will see how this is possible!

How Does It Work?

Most request smuggling vulnerabilities arise because the HTTP specification provides two different ways to specify where a request ends: the Content-Length header and the Transfer-Encoding header.

Given this specificity, it's possible for the same message to use both methods simultaneously, causing them to conflict with each other.

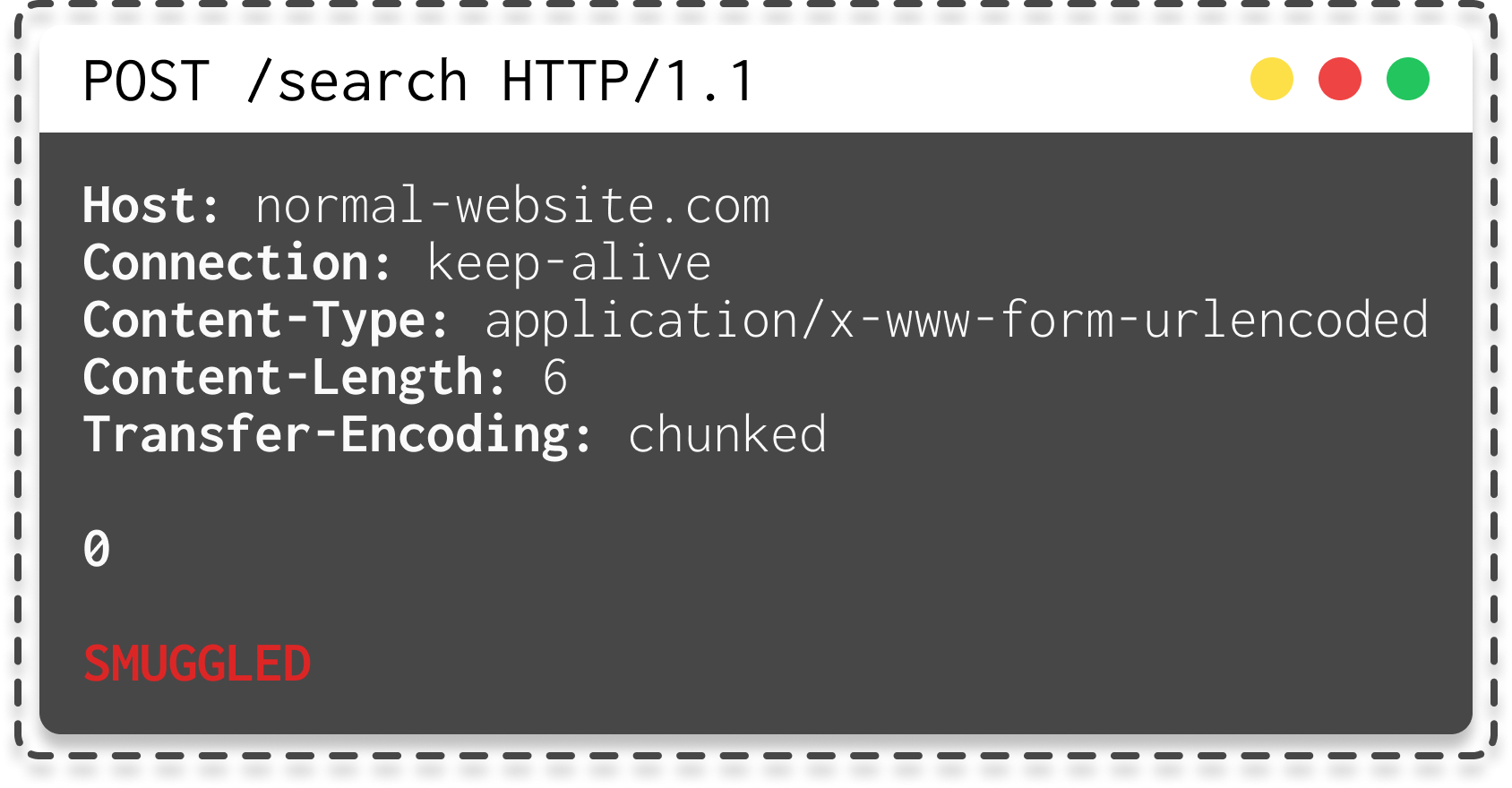

Request smuggling involves placing the Content-Length header and the Transfer-Encoding header in a single HTTP request and manipulating them in a way that the frontend and backend process the request differently.

Let's take this HTTP request as an example:

|

|---|

| HTTP POST Request |

As you can see, even though the two servers use a different header to determine the size of the request, everything works smoothly.

|

|---|

| Behavior of Two Servers Regarding This HTTP Request |

But what happens if an attacker adds a second header indicating the size at the end of the request?

He will add the Transfer-Encoding header, which is used to specify that the message body uses chunked encoding.

This means that the message body contains one or more chunks of data. Each chunk consists of the chunk size in bytes (in hexadecimal), followed by a newline, and then the content of the chunk. The message ends with a zero-sized chunk.

|

|---|

| HTTP Request for Performing Request Smuggling |

So, what happens?

As you can see in the GIF, the front-end server processes the Content-Length header and determines that the request body is 6 bytes long, ending at SMUGGLED. This request is forwarded to the backend.

The backend processes the Transfer-Encoding header and, therefore, treats the message body as using this header.

It processes the first chunk, which is declared as having zero length and is, therefore, considered to end the request (because of \r\n0\r\n\r\n). The subsequent bytes, SMUGGLED, are not processed, and the backend server considers them the start of the next request in the sequence. So, SMUGGLED is treated as a new request, and it would be possible to include a payload like "GET /admin" to bypass the frontend and access the admin panel.

|

|---|

| Operation of Request Smuggling |

There are several types of request smuggling based on the behavior of the two servers:

- CL.TE: The front-end server uses the Content-Length header, and the back-end server uses the Transfer-Encoding header.

- TE.CL: The front-end server uses the Transfer-Encoding header, and the back-end server uses the Content-Length header.

- TE.TE: Both the front-end and back-end servers support the Transfer-Encoding header, but one of the servers can be persuaded not to process it by obfuscating the header in some way.

Now that request smuggling is clearer to you, let's move on to the demonstration!

Impacts

- Security Bypass: Request smuggling can allow an attacker to bypass security controls implemented on a web server. This can include bypassing web application firewall (WAF) rules and other security mechanisms, thereby granting the attacker access to unauthorized resources.

- Exposure of Sensitive Data: By exploiting a request smuggling vulnerability, an attacker can gain access to sensitive or confidential data. This may include user personal information, financial data, or any data that should be protected.

- Data Tampering: Request smuggling can enable an attacker to manipulate data transmitted between the client and the server. This can lead to undesired data modifications, content tampering, or even man-in-the-middle attacks where an attacker intercepts and modifies data in transit.

- Application Logic Alteration: By exploiting a request smuggling vulnerability, an attacker can alter the application logic and bypass authorization controls or security mechanisms. This can allow them to access features or actions normally restricted.

Remediation Measures

To prevent vulnerabilities related to request smuggling, here are the measures to follow:

- Use HTTP/2 end-to-end and disable HTTP downgrade if possible. HTTP/2 employs a robust mechanism for determining request length, and when used end-to-end, it is inherently protected against request smuggling. If you cannot avoid HTTP downgrade, ensure validation of the rewritten request against the HTTP/1.1 specification. For example, reject requests containing newlines in headers, colons in header names, and spaces in the request method.

- Ensure that the front-end server normalizes ambiguous requests and that the final server rejects those that are still ambiguous, closing the TCP connection in the process.

- Never assume that requests will have no bodies. This is the root cause of CL.0 vulnerabilities and client-side desynchronization.

- Drop the default connection if server-level exceptions occur during request processing.

Resources

http-smuggling | makina-corpus

HTTP-keep-alive | imperva

HTTP request smuggling| portswigger

http-request-smuggling | thehacker.recipes