HTTP for dummies

Introduction

I was originally going to make a blog post about request smuggling, a vulnerability related to HTTP, but putting together the explanation of the protocol and the explanation of the vulnerability in one post is too long.

So let's vulgarize HTTP !

HTTP stands for Hyper transfer text protocol. HTTP is a communication protocol used to exchange data over the Web.

A client/server affair

HTTP works as a client/server. Here's a quick analogy to help you understand

Let's imagine that in a restaurant, the customer sends a request to the restaurant's server (server) for a particular dish (a web resource, e.g. a page) using the menu (the web page you're on). The server then responds with the requested dish (the resource).

|

|---|

| Client/server affair |

Just as the client can make several requests for different dishes, the browser can also make requests for different resources, such as images, web pages or videos. The server will respond to each request with the appropriate answer, just as a restaurant waiter would bring the requested dish to the table.

What's more, just as a restaurant can have different tables for different customers, a web server can handle multiple requests from different customers at the same time, serving different resources to each customer.

|

|---|

| Multiples requests |

State-what ? Stateless ?

You may have heard the term STATELESS before, but you don't necessarily understand what it means for HTTP.

Let's take the example of a flight booking application. When a user performs a search for available flights, the server returns a list of results corresponding to the user's search criteria. If the user performs a new search for a different flight, the server doesn't remember the results of the previous search.

|

|---|

| Stateless example |

In short, the "stateless" nature of HTTP means that each request is independent and doesn't retain information about previous requests, enabling greater scalability and optimization of server resources.

Nevertheless, many web applications do provide status, through cookies and session management, such as shopping carts and online shops.

URL, URI, what's the difference ?

Another point I wanted to address was the difference between URLs and URIs. Before the post, I had a tendency to get confused, so I thought if it's useful for me, maybe it'll be useful for you too!

URLs and URIs are identifiers used to locate resources on the Web.

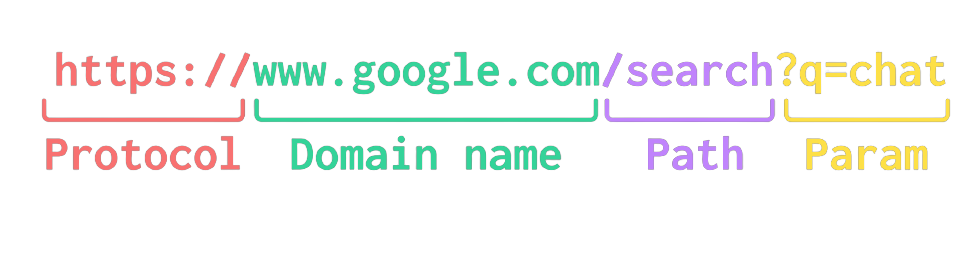

- A URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is a Web address that identifies the location of a specific resource on the Internet, such as a Web page, an image or a downloadable file. It includes the domain name, the protocol used to access the resource (HTTP, HTTPS, FTP, etc.), the file path and sometimes query parameters.

|

|---|

| URL example |

- A URI (Uniform Resource Identifier) is a generic identifier for an Internet resource. It can be used to identify a resource in a number of ways, including using a URL.

The difference with a URL is that a URI can also identify a resource using a unique name or address, even if the resource is not accessible online.

For example, the name of a book can be used as a URI to identify that book, even if it is not online.

|

|---|

| URI example |

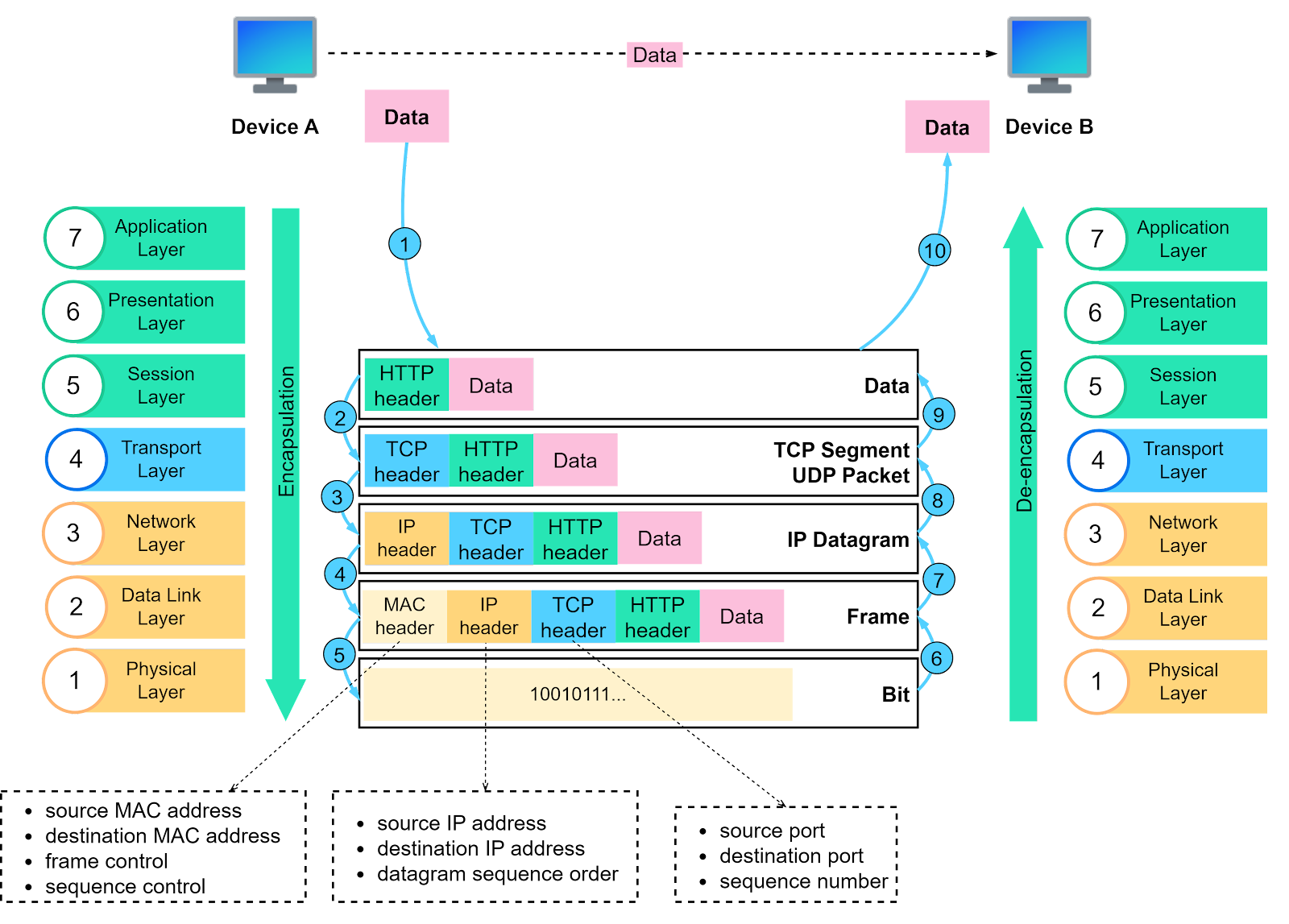

Dear OSI model

OSI stands for Open System Interconnection, and is the reference model for computer-to-computer communication.

I won't go back over the 7 layers of the OSI model, but you should know that HTTP is located on the highest layer of the OSI model, the application layer.

|

|---|

| OSI Model |

99.9% of the time, HTTP uses TCP/IP as its transport protocol (unlike UDP).

We won't go into the details of the TCP protocol in this post, but simply, TCP defines how data is formatted, then sent from point A to point B.

However, as HTTP is on a layer above the transport layer, it doesn't care about all that. For HTTP, the only thing that matters is :

I want a resource, the server sends me a response

Now that we've covered the basics, let's take a look at what makes up an HTTP request, starting with the first term, the HTTP VERB.

HTTP Verbs

HTTP verbs, also known as HTTP methods, are used to indicate the action to be performed on a resource during an HTTP request.

- GET: This is the most common verb, used to retrieve a resource from a remote server.

- For example, when accessing a web page such as toto.fr, the browser sends a GET HTTP request to retrieve the page hosted on the server, i.e. toto.html.

|

|---|

| Get example |

- POST: This verb is used to send data to the server in order to create a new resource.

- Let's imagine that on toto.fr, there's a form to add a blog post. By clicking on "POST", the browser will send a POST request containing the data from the form, so that the server can create a new entry in the database, and therefore a new post on the blog. In web pentesting, POST requests, because they send data to the server, are often a much-used attack vector.

|

|---|

| Post example |

- PUT: This verb is used to update an existing resource on the server. For example, on toto.fr, you can log in and access your profile. If you want to update your first and last names, the browser will send a PUT request containing the changes to the server.

- DELETE: Quite explicit, this command deletes a resource from the server. For example, if you delete your account on toto.fr, the browser will send an HTTP request with DELETE.

These are the main HTTP verbs, others exist, but we'll quickly go over them :

- HEAD: similar to GET, but the server returns only the response headers, without the body. This verb is often used to check whether a resource has been modified since the last request.

- OPTIONS: used to obtain the communication options available for a resource, such as the HTTP verbs supported by the server.

|

|---|

| Options example |

- PATCH: used to perform a partial update of a resource. Instead of replacing the entire resource, the server updates only the parts specified in the request.

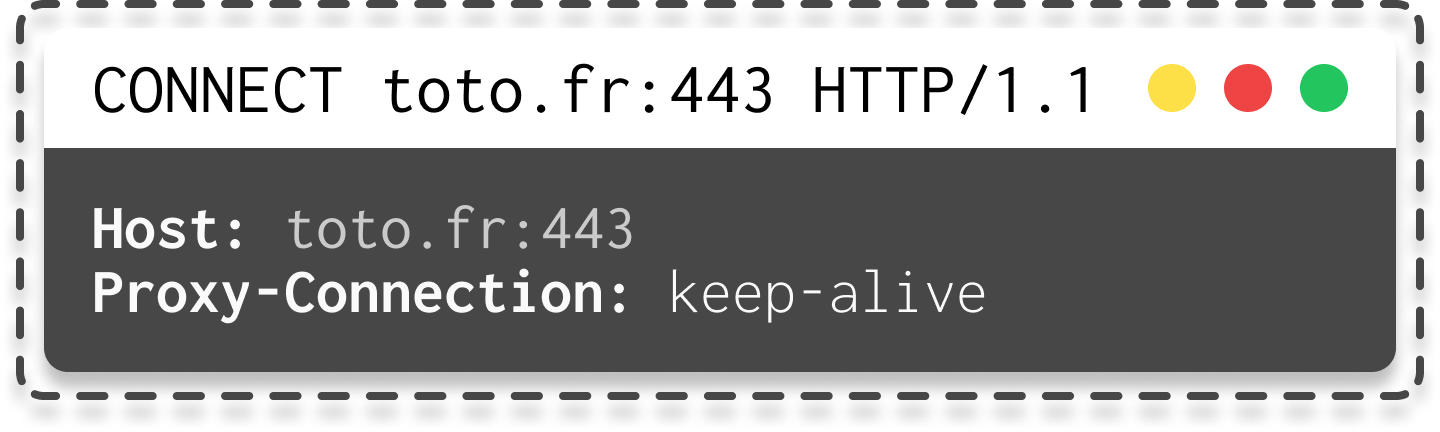

- CONNECT: used to establish a tunneled network connection to the server, typically for SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) connections.

|

|---|

| Connect example |

- TRACE: used to retrieve a request callback loop, enabling a request to be tracked or debugged, can lead to vulnerabilities such as Cross Site Tracing.

Requested Ressource

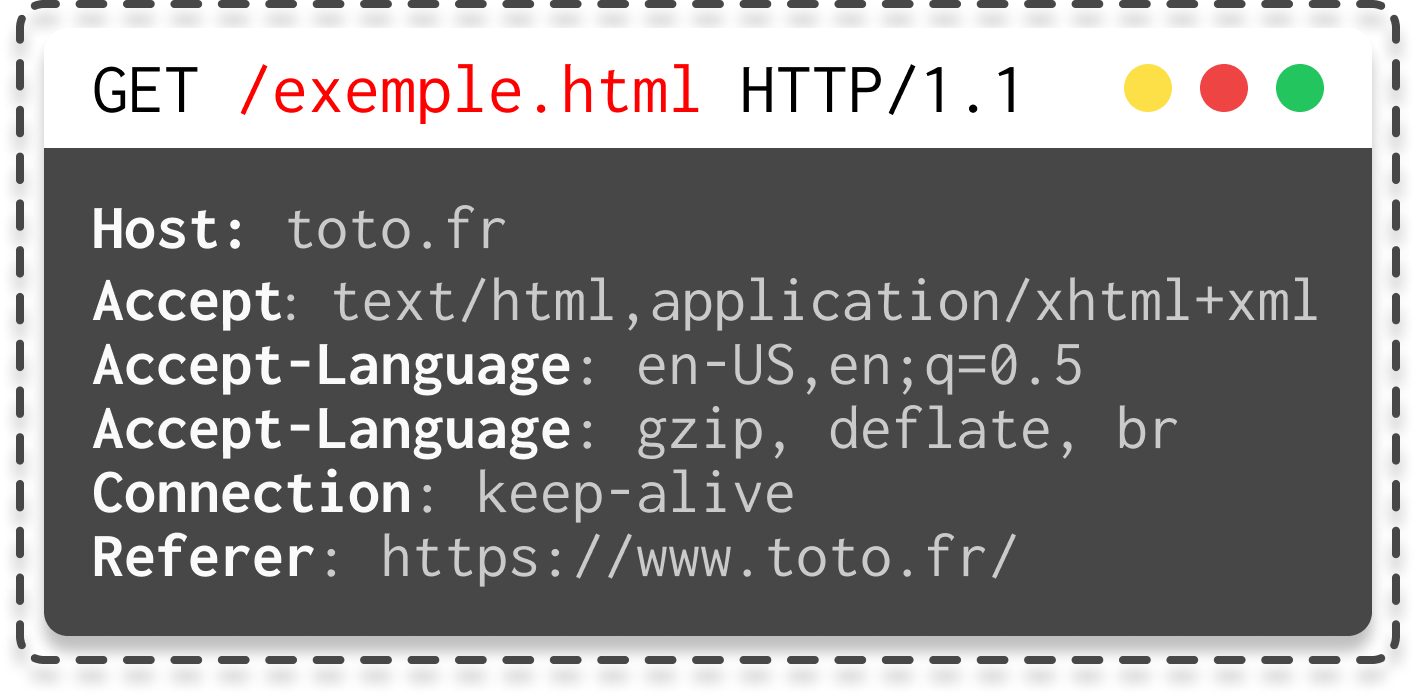

Once you've defined the verb, you need to tell the server which resource you want, as you can see.

|

|---|

| Path in red |

HTTP Version

Once you've chosen the resource you want, you need to tell the server which version of HTTP you want to use.

Today, HTTP version 1.1 is the most common on the web, with HTTP version 2 on the rise.

The history of HTTP versions could be the subject of a whole blog post, but just remember that in :

- Version 0/9, each request opened a TCP/IP connection, which wasn't very optimised, and only the verb is the resource was present.

- Version 1/0 introduced headers, which we'll see later.

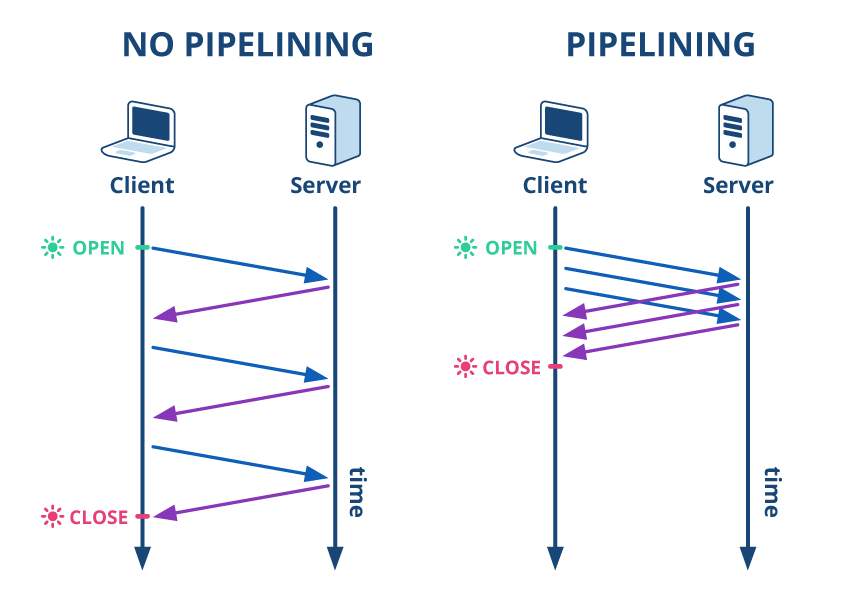

- Version 1/1 introduced pipelining, a simple principle enabling multiple requests to be sent BEFORE the responses are received.

|

|---|

| HTTP pipelining |

- Version 2 introduced binary rather than text encoding, and protocol multiplexing to manage multiple requests within a single TCP/IP connection (the keep-alive header made this possible in 1/1, but that's it).

HTTP Headers

HTTP headers are additional information sent with an HTTP request or response. These headers contain information such as content type, encoding, language, browser used and other information relevant to processing the request or response.

For example:

- A Content-Type header indicates the type of content sent or received, such as text, image or video.

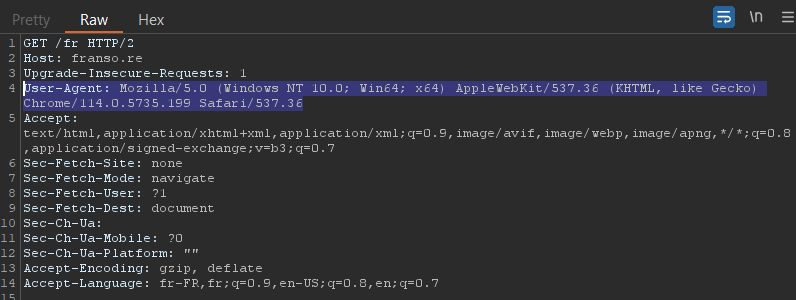

- A User-Agent header indicates the browser or application used to send the request.

|

|---|

| User-Agent header example |

- An Accept-Language header indicates the client's preferred language for the response.

HTTP headers are important because they enable the server and client to communicate in greater detail about the information being sent or expected. This enables better management of requests and responses, a better understanding of the client's needs and better security by specifying certain restrictions or authorizations.

Now that we've seen everything that makes up a request, let's move on to the response!

Response code

Once your request has been sent, several responses are possible. These responses contain a code called the HTTP response code.

This is a three-digit code sent by an HTTP server to indicate the result of a request made by a client.

There are five categories of HTTP response codes: 1xx, 2xx, 3xx, 4xx, and 5xx.

- HTTP response codes in the 1xx series are information responses and are used to indicate that the server has received the client's request and is continuing to process it.

- For example, 101 (Switching Protocols) indicates that the server has accepted the protocol switching proposal sent by the client.

- HTTP response codes starting with 2xx indicate that the request has been processed successfully.

- For example, HTTP response code 200 means that the request has been processed successfully and that the response contains the requested information.

- HTTP response codes beginning with 3xx indicate a redirection.

- For example, HTTP response code 301 indicates that the requested resource has been permanently moved to a new address, and that the client needs to update its URL.

- HTTP response codes starting with 4xx indicate an error caused by the client.

- For example, HTTP response code 404 means that the requested resource was not found on the server.

- HTTP response codes starting with 5xx indicate an error caused by the server.

- For example, HTTP response code 500 means that an error occurred on the server side when processing the request.

Resources

network-protocols-run-the-internet | bytebytego

http-keep-alive-pipelining-multiplexing-and-connection-pooling | haproxy

Hypertext_Transfer_Protocol | wikipedia

HTTP | mozilla